Located near Cusco, Tipon isn’t mind-blowing like Machu Pic’chu or Ollantaytambo. But it is an amazing place.

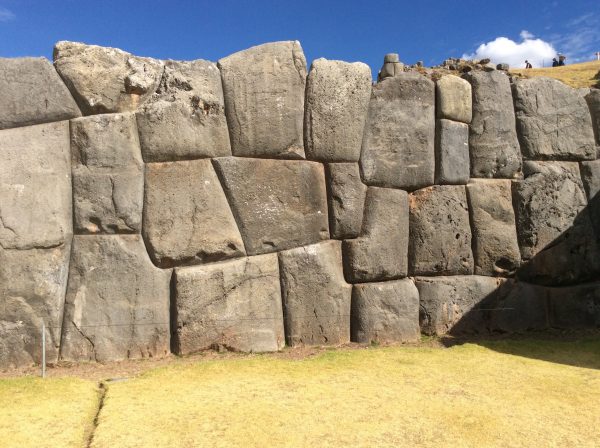

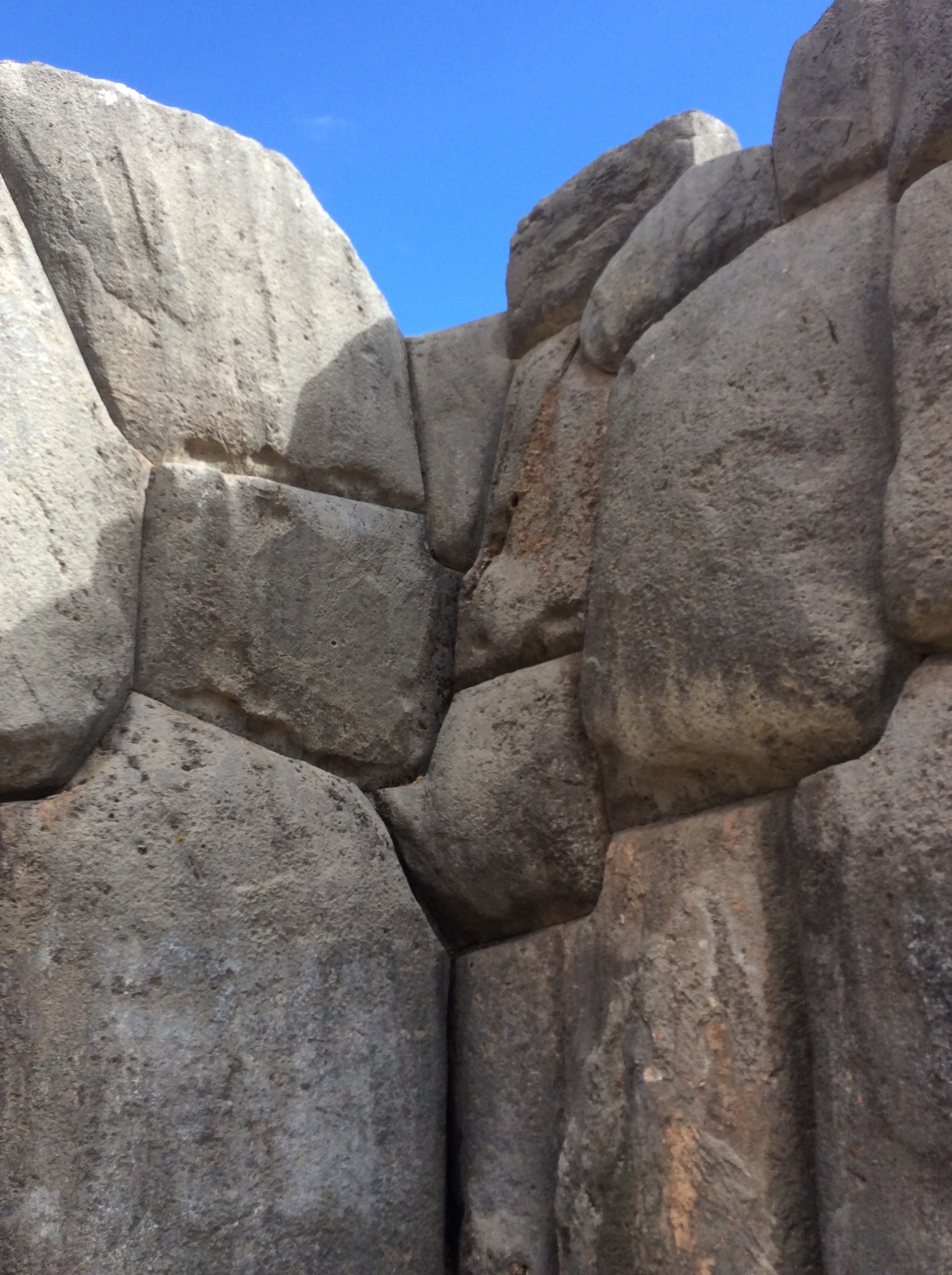

I realize I’ve been kind of slamming the Incas: not because they were incapable of the megalithic work they built on, which is technologically more advanced than anything we can do even now, but because of the “stupid history” that gives them credit for work they could not possibly have done.

I didn’t show it yesterday, but here’s the side of the cave opposite the megalithic “portal.” Megalithic “altar” behind the dude with the hat.

Tipon has a number of well-watered terraces, a collection of microclimates. But your first introduction is a small gurgling waterfall.

Channeled from another waterfall.

And then you realize there are many of them, on every wall, every corner.

Our guide, shaman Dr. Theo Paredes, urged us to pay attention to the distinct sounds of each. When I observed many empty streams (the walls above and to the left), he explained that work was being done on the aqueduct from the source, 2 km away. I could only imagine that with all flowing, the atmosphere must be magic. As it was, all who visited left feeling energized.

Near the very top, the water enters through four streams. Simple, yes?

No! The water enters as one stream, which is divided into two streams, which recombine to one stream, which is then fanned out into four channels (that is not just perspective; the final four streams are farther apart at the end than the beginning).

As Theo tried to explain, what’s going on here is a profound understanding of energies we tend to ignore. Given his credentials — struck by lightning twice, first time at age 11 — I am happy to accept his word that more is happening here than I perceive.

So it was a place of healing as well as agriculture. And it wouldn’t have been monochromatic — amazing to imagine the effect of the water and geometry with the terraces planted in vibrant colors. Why not?

Now, meet Irma Gutierrez de Aparcana, age 78, here demonstrating how she has been making the Ika stones for the last 61 years.

Now, meet Irma Gutierrez de Aparcana, age 78, here demonstrating how she has been making the Ika stones for the last 61 years.