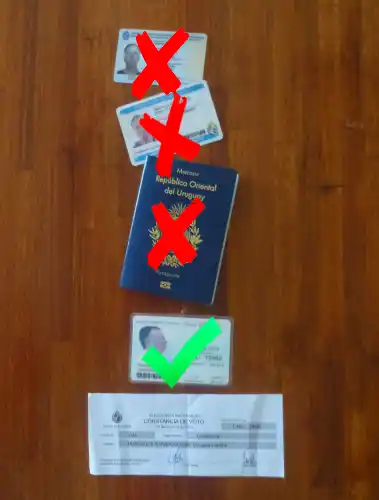

In order to vote in national elections in Uruguay–required of adult citizens–you cannot present

- driver’s license

- national ID (cédula)

- passport

You must instead produce a special ID specifically for voting, the credencial civica. When you have voted, you get a slip of paper (constancia de voto).

Your series and number on the credencia civica determine your voting place. For us, it’s a high school on the other side of the Ruta Interbalnearia. There are two closer school polling places. We can’t get to ours without passing directly in front of one or the other. Go figure.

Once there, you go into one of two buildings, depending on your number, then the range is further divided into classrooms. Inside is a soldier, and three people behind desks. You take a voting envelope, and one reads your number and the ballot number. A second person crosses your name off the list of voters, while the third records the ballot number on an electronic tablet.

You then go behind a shielded area where desks are strewn with ballots for various candidates, some of whom appear on more than one numbered list. No, I’m not even going there. I haven’t yet heard an explanation that makes sense. You put your ballot in the envelope and seal it (just in case, you might have picked up a ballot outside or at various stands the weeks before, since there’s no guarantee one will be available). You then return to the front desks, tear off the perforated ID portion of the envelope for person #3 while person #1 lifts a folder to reveal the slot in the ballot box where you stick the now-anonymous envelope.

I don’t know the details of counting, but I suspect they are equally meticulous.

It may all sound a bit clunky, but there’s something about the soundness of the process that a certain country, whose name also begins with U, which has 100 times the population of Uruguay, could learn from.